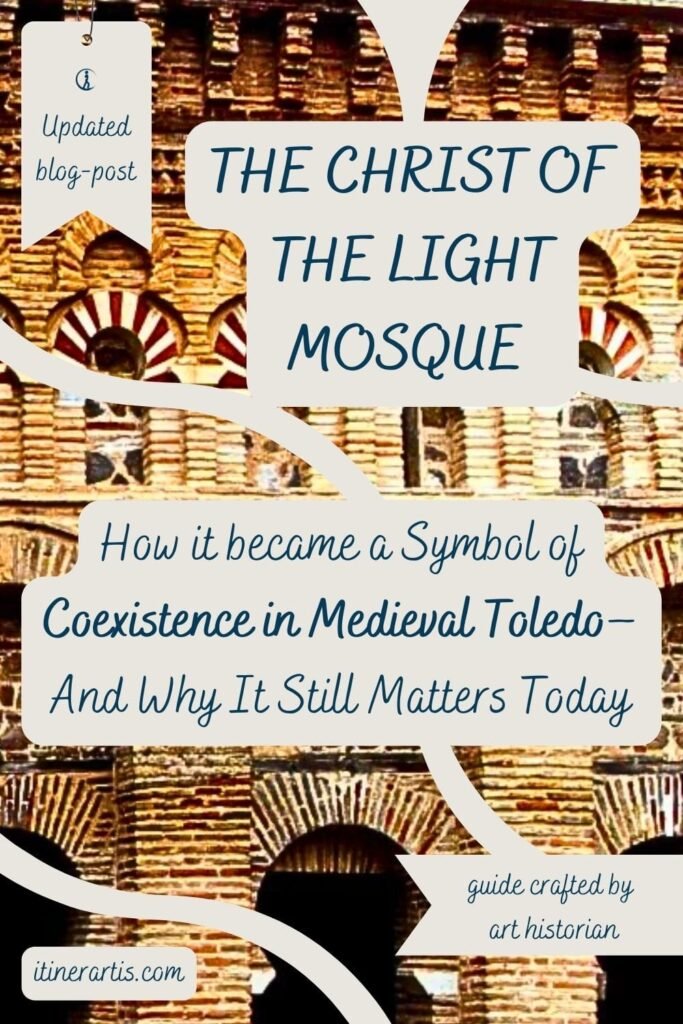

How the Christ of the Light Mosque in Toledo became a Symbol of Coexistence – And Why It Still Matters Today

If you are wondering how the words “mosque” and “Christ” can fit in the name of the same building, Toledo holds the answer. Tucked behind the medieval Puerta del Sol, the Christ of the Light Mosque has endured for over a thousand years, bridging cultures and faiths. Modest in scale but rich in history, it does not seek to impress with grandeur. Instead, it surprises with its survival, standing as a quiet witness to Toledo’s shifting rulers, from the Islamic caliphs to the Christian kings who followed.

Built in 999 CE, when Al-Andalus thrived as a center of knowledge and artistry, the mosque reflected the architectural brilliance of Córdoba. But in 1085, Toledo fell to Alfonso VI. Many mosques vanished, either destroyed or transformed beyond recognition. This one did not. A Christian apse was added, yet the Arabic inscription, the horseshoe arches, and the ribbed vaults remained untouched. Over time, stories emerged—whispers of a hidden relic, a miraculous discovery—woven into the building’s layered history.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage site, the Christ of the Light Mosque is more than just a historical relic. It is a dialogue in stone. A rare instance where the past was not erased, but layered. Where conquest did not mean destruction. And where art transcended the boundaries of faith. Its walls, weathered yet intact, invite visitors to step into a space where history is not black and white, but an intricate pattern of light and shadow.

Post last updated on March 17, 2025 (originally published on September 25, 2022) by Roberta Darie.

- Where Is the Christ of the Light Mosque?

- What Makes the Christ of the Light Mosque Special?

- The Story Behind the Stones: The Transformation of the Christ of the Light Mosque

- What to See when Visiting the Christ of the Light Mosque

- The Ribbed Vaults: A Sky of Stone and Light

- The Horseshoe Arches: A Dance of Light and Shadow

- The Sebka Façade: The Geometry of Al-Andalus

- The Mudéjar Apse: A Fusion of Two Faiths

- The Mural Paintings: A Testament to Toledo’s Multi-Faith Legacy

- Restoring the Past: The Frescoes Reclaimed

- The Archaeological Layers Beneath the Christ of the Light Mosque in Toledo

- Activities: What Else to Do Near the Christ of the Light Mosque?

- When to Visit & How Long to Stay

- Final Thoughts – Why the Christ of the Light Mosque Still Matters Today

“Instead of cursing the darkness, light a candle.”

Benjamin Franklin

Where Is the Christ of the Light Mosque?

Hidden in the labyrinthine streets of Toledo’s historic quarter, the Christ of the Light Mosque sits near the Puerta del Sol, once known as Bab al-Mardum — “the sealed gate” in Arabic. This was one of the main entry points to the medieval city, where traders, scholars, and pilgrims once crossed paths. Today, it leads visitors into a layered past, where Roman, Visigothic, and Islamic influences converge.

The mosque, dating from 999 CE, is one of the oldest and best-preserved Islamic structures in Spain. Its Kufic inscription, still on the façade, names its patron, Ahmad ibn Hadidi, and the artisans who constructed it. Unlike many mosques that were drastically altered or rebuilt, this one retains its original layout. Offering an unaltered glimpse into the religious architecture of Al-Andalus. The Mudéjar apse, added in the 12th century, transformed it into a Christian chapel without erasing its essence.

Despite standing within a UNESCO-listed historic city, the Christ of the Light Mosque remains surprisingly understated. It doesn’t compete with Toledo’s cathedral or Alcázar for attention. Instead, it rewards those who seek it out, offering an intimate journey into a time when art, science, and faith intertwined.

What Makes the Christ of the Light Mosque Special?

In a city of towering cathedrals and grand fortresses, the Christ of the Light Mosque is easy to overlook. Modest in size, tucked away near Toledo’s ancient walls, it doesn’t demand attention. However, it rewards those who pause. Step inside, and you enter a world where time folds in on itself. Nine ribbed vaults rise above, their delicate interlacing a quiet echo of Córdoba’s Great Mosque. Slender columns stand firm, their capitals carved centuries before the mosque was even built. Look closely—these aren’t just any columns. They belonged to a Visigothic church, long forgotten, yet still here.

Most mosques in Christian Spain were either dismantled or swallowed by towering Gothic churches. But this one remained. Instead of erasing its past, Toledo layered it. A small apse was added, its Mudéjar brickwork seamlessly blending into the original structure. The Arabic inscriptions, once prayers in a different faith, still stand untouched. Even after its conversion, the space still carries the rhythm of its first architects. Light filtering through high windows, shifting across ancient patterns.

But there’s something else here, something unspoken. A whispered legend. A king, a hidden relic, a lamp that burned for centuries. A myth that secured the mosque’s survival. And in doing so, the Christ of the Light Mosque became something rare. Not just a building, but a bridge between worlds, where faiths met not in conflict, but in stone and light.

The Story Behind the Stones: The Transformation of the Christ of the Light Mosque

Like all great monuments, the Christ of the Light Mosque has lived many lives. Built at the height of Al-Andalus, it later witnessed conquest, adaptation, and even a legend of divine intervention. This is not just a structure: it is a living archive of Toledo’s layered past where Islamic and Christian influences intertwine, creating one of the most fascinating architectural fusions in Spain.

A Mosque Born in the Golden Age of Al-Andalus

In 999 CE, when Toledo was a thriving intellectual hub, a wealthy Muslim patron, Ahmad ibn Hadidi, commissioned a small mosque near the Bab al-Mardum gate. Designed by Musa ibn Ali, its architecture reflected the height of Caliphal style, mirroring the great monuments of Córdoba.

It was not a grand congregational mosque, but a private oratory, likely serving a small community of scholars and traders who entered the city through its northern gate. The horseshoe arches, interwoven brick patterns, and Kufic inscriptions on the façade embodied the artistic and scientific sophistication of Al-Andalus.

The Christian Takeover & the Legend of the Eternal Light

In 1085, King Alfonso VI of Castile reclaimed Toledo from Muslim rule. According to legend, as his army passed by the mosque, his horse mysteriously knelt at its entrance. When the king ordered an excavation, a hidden crucifix and an oil lamp were discovered—said to have burned continuously for 300 years, untouched throughout Islamic rule. This was considered a divine sign, and the mosque was converted into a Christian chapel.

By 1186, Alfonso VIII granted it to the Knights Hospitaller, who expanded it with a Mudéjar-style apse. Unlike most former mosques, its core structure remained largely intact, making the Christ of the Light Mosque a rare example of the coexistence of faiths that defined medieval Toledo.

What to See when Visiting the Christ of the Light Mosque

Stepping into the Christ of the Light Mosque is like entering a living manuscript of Spain’s past. Every arch, vault, and inscription reveal a chapter of faith, artistic innovation, and survival. Though modest in size, this mosque-turned-chapel is a masterpiece of Visigothic, Caliphal, and Mudéjar architecture. Here’s what makes it truly remarkable:

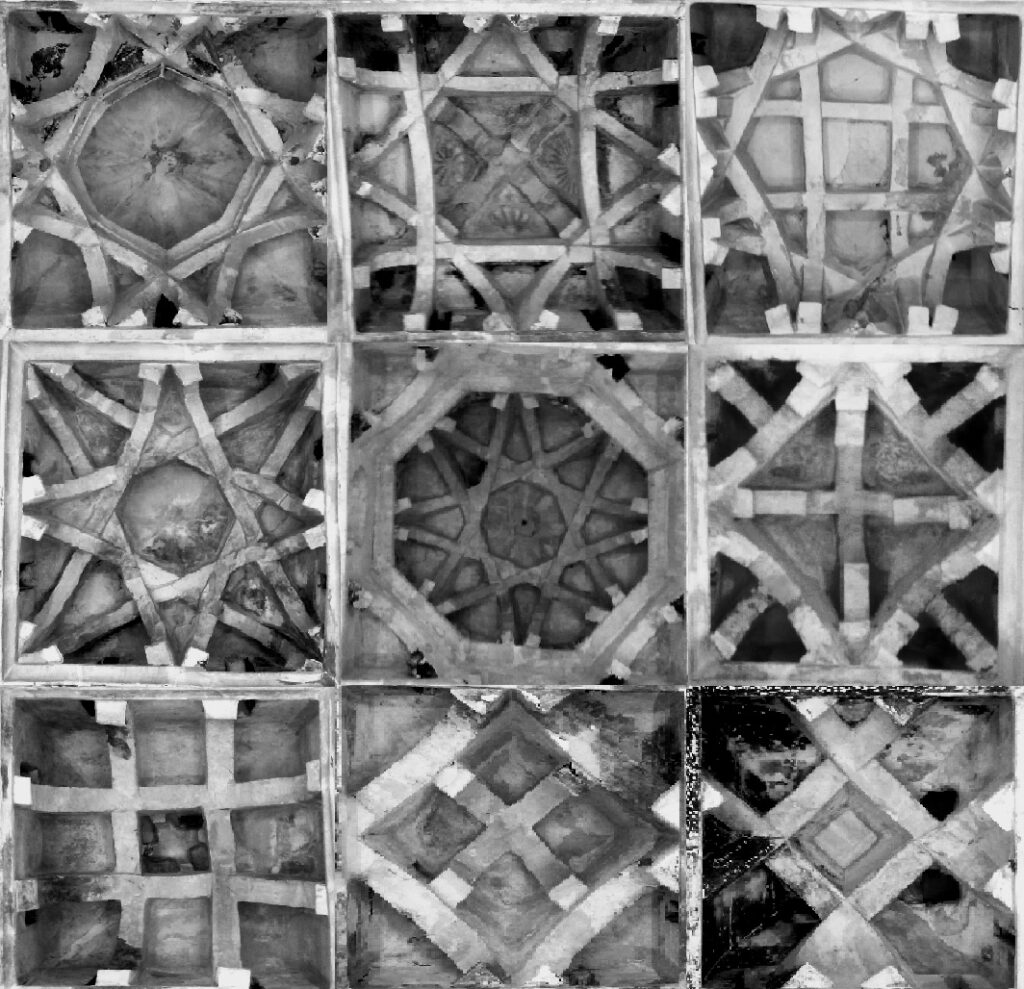

The Ribbed Vaults: A Sky of Stone and Light

Step inside the Christ of the Light Mosque, and your eyes are naturally drawn upward. Above you, nine distinct ribbed vaults stretch across the ceiling, their interlacing patterns forming a celestial geometry. These domes, inspired by the Great Mosque of Córdoba, showcase the architectural brilliance of 10th-century Al-Andalus.

Their design is both structural and aesthetic—light filters through high openings, casting shifting shadows that animate the space throughout the day. The central dome, slightly elevated, subtly marks the spiritual core of the building, creating a sense of sacred presence.

However, what makes these vaults remarkable is their mathematical precision. Unlike the simpler barrel vaults of early medieval Europe, these ribs weave into star-like patterns, foreshadowing Gothic innovations. The builders, likely trained in Córdoba’s royal workshops, turned the Christ of the Light Mosque into a miniature architectural laboratory. Even after its conversion into a Christian chapel, these vaults remained untouched—a silent tribute to their timeless beauty.

The Horseshoe Arches: A Dance of Light and Shadow

Step into the Christ of the Light Mosque, and you’ll find yourself surrounded by an intricate interplay of curves and space. The horseshoe arches, a defining feature of Umayyad architecture, create a rhythmic elegance that makes the small interior feel expansive. These arches, characteristic of Al-Andalus, are more than decorative. They serve a structural and symbolic purpose. They frame the nine domed bays, reinforcing the sense of harmony that defines the mosque’s layout.

Furthermore, the columns supporting them, repurposed from earlier Visigothic structures, reveal Toledo’s layered history. Here, one civilization quite literally built upon another.

Light and shadow dance through these arches, shifting as the day progresses. The softened glow filtering through high windows creates a sense of movement, emphasizing the fluidity of Islamic design. Each arch draws the eye upward, giving the impression of greater height within the compact space. This architectural illusion, common in Islamic prayer halls, invites contemplation, mirroring the spiritual aspirations of those who once prayed here.

The Sebka Façade: The Geometry of Al-Andalus

From the outside, the Christ of the Light Mosque reveals yet another artistic triumph: its sebka-patterned façade. This intricate latticework of interlocking diamonds, crafted in brick, is one of the earliest examples of a motif that would later define Almohad and Nasrid architecture.

The geometric precision foreshadows the dazzling ornamentation of the Alhambra in Granada, making this mosque a crucial link in the evolution of Andalusian design. Beyond aesthetics, sebka patterns manipulate light, casting ever-changing shadows that animate the façade. A dynamic expression of the architectural brilliance of Al-Andalus.

The Mudéjar Apse: A Fusion of Two Faiths

After Toledo’s conquest in 1085, the Christ of the Light Mosque underwent a transformation, yet its Islamic architectural core remained largely untouched. Instead of being demolished or heavily altered, it was repurposed into a Christian chapel, a practice common in medieval Spain.

The most significant addition was the Mudéjar-style apse, built in the 12th century. Mudéjar architecture, a unique fusion of Islamic craftsmanship and Christian patronage, was the artistic language of Toledo’s religious coexistence.

The apse, constructed with brick and decorated with blind arches, seamlessly integrates into the original mosque, demonstrating how two faiths coexisted within the same sacred space. This blend of forms is not just an architectural decision. It is a historical statement, showing that adaptation, rather than destruction, often defined the transition between cultures in medieval Spain.

The Mural Paintings: A Testament to Toledo’s Multi-Faith Legacy

Inside the Christ of the Light Mosque, beneath arches that once framed Muslim prayers, a remarkable discovery was made in 1871. Hidden under centuries of whitewash, a set of 13th-century Romanesque frescoes emerged, revealing the mosque’s layered history. These murals, painted after the building’s conversion into a Christian chapel, intended to claim the space for Christianity.

At the center, Christ Pantocrator sits enthroned within a celestial mandorla, his right hand raised in blessing. Around him, symbols of the four Evangelists—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—once stood, though time has softened their details. Beneath this imposing figure, Saint Ildefonso and Saint Eugenio, two of Toledo’s most revered bishops, act as silent witnesses to the city’s Christian heritage.

Restoring the Past: The Frescoes Reclaimed

Despite their Christian iconography, the frescoes retain traces of Islamic artistic influence. The geometric framing, pseudo-Kufic inscriptions, and arabesque motifs suggest the hand of Mudéjar artisans, whose work blended Islamic aesthetics with Christian narratives.

The color palette—deep blues, ochres, and earthy reds—enhances the ethereal quality of the paintings. In 2014, a meticulous restoration project revived these murals, bringing back their original vibrancy while preserving the patina of time. Today, these frescoes stand not only as works of religious art but as a bridge between faiths, reminding visitors that the Christ of the Light Mosque is not just a building, but a living chronicle of Toledo’s multicultural past.

The Archaeological Layers Beneath the Christ of the Light Mosque in Toledo

Beneath the Christ of the Light Mosque, history runs deep—literally. During restorations, archaeologists uncovered a 5-meter-wide (16-foot) Roman road, its granite slabs worn smooth by centuries of travelers. Alongside it lay a Roman sewer, an engineering feat of opus caementicium, the same material that built aqueducts and amphitheaters across the empire. These finds reveal that long before Toledo became a city of mosques and cathedrals, it was a Roman stronghold, its streets echoing with the footsteps of merchants and soldiers.

But the most astonishing discovery lay hidden beneath the Mudéjar apse—the remains of an older apse and a crypt, possibly from a late Roman or Visigothic church. This supports an age-old legend: that a Christian shrine once stood here, concealed when the city fell to Muslim rule. Instead of erasing history, each era built upon the last, aligning their sacred spaces in an unbroken line of faith.

Today, visitors can glimpse these ancient layers—the Roman road, the Visigothic remnants—woven into the very foundation of the mosque. It is a rare place where history is not just preserved but revealed, where the past is quite literally beneath your feet.

Activities: What Else to Do Near the Christ of the Light Mosque?

Toledo is a city that demands to be explored on foot. Narrow streets wind through centuries of history, each turn revealing a new layer of its Islamic, Christian, and Jewish past. Once you’ve stepped inside the Christ of the Light Mosque and traced the stories embedded in its walls, there’s more to uncover nearby.

Follow the Footsteps of the Three Cultures in Toledo

Toledo has long been known as the “City of Three Cultures”, where Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities coexisted for centuries. Just a short walk from the mosque, you’ll find Santa María la Blanca, a 12th-century synagogue that later became a church.

Its horseshoe arches and whitewashed columns bear the unmistakable influence of Islamic art, even though it was built for a Jewish congregation. A few streets away, El Tránsito Synagogue, now the Sephardic Museum, houses some of the best-preserved Mudéjar decoration in Spain, with delicate geometric carvings and Hebrew inscriptions woven into the walls.

Walk the City Walls & Gates of Toledo

The Puerta del Sol, just steps from the Christ of the Light Mosque, was once an essential entry point into medieval Toledo. From there, a short walk leads to the Puerta de la Bisagra, the grand gateway built by the Moors and later expanded by the Habsburgs. Standing before its massive stone towers, you can almost hear the distant echoes of traders, soldiers, and pilgrims who once crossed its threshold.

Explore the Alcázar & Toledo Cathedral

For a deeper dive into Toledo’s Christian legacy, visit the Alcázar of Toledo, an imposing fortress that has guarded the city for centuries. Then, step inside the Toledo Cathedral, a masterpiece of Gothic architecture, where light filters through stained-glass windows nearly 30 meters high (ca. 98 feet). The contrast between this monumental cathedral and the intimate Christ of the Light Mosque tells the story of Toledo’s evolving spiritual landscape.

Visit the Mirador del Valle

For the best panoramic view of Toledo, head to the Mirador del Valle, located just outside the city center. As the sun sets over the Tagus River, the city’s skyline—dominated by the Alcázar, the cathedral, and the winding medieval streets—glows in warm golden hues. It’s a sight that reminds visitors why Toledo, much like the Christ of the Light Mosque, remains one of Spain’s most compelling historical destinations.

When to Visit & How Long to Stay

Timing is everything when visiting a city as steeped in history as Toledo. The medieval streets, sun-drenched plazas, and quiet corners of the Christ of the Light Mosque offer a different experience depending on the season. To fully appreciate its details—the interplay of light on its intricate ribbed vaults, the contrast between Islamic arches and Mudéjar apse—it’s best to avoid the extremes of Toledo’s climate.

Best Time to Visit the Christ of the Light Mosque in Toledo

Spring (March–May) and autumn (September–November) are ideal. During these months, temperatures range between 15–25 °C (59–77 °F), making long walks through Toledo’s historic quarter more enjoyable. The city is also less crowded compared to summer, allowing for a quieter, more immersive experience inside the Christ of the Light Mosque. Morning visits are particularly magical, as the soft light filters through its small windows, casting intricate shadows that bring the architecture to life.

Summer (June–August) can be challenging. Toledo, like much of inland Spain, experiences temperatures exceeding 35 °C (95 °F), and the lack of shade in the city’s stone-paved streets can make walking exhausting. If you visit in summer, explore early in the morning or late in the afternoon.

How Long to Stay in Toledo

A one-day visit is barely enough to see Toledo’s highlights, including the Christ of the Light Mosque, the Toledo Cathedral, and the Alcázar. However, a two-day or weekend stay allows for a deeper dive into the city’s layers of history. With more time, you can explore its lesser-known corners—hidden courtyards, museums, and the former Jewish quarter, where Toledo’s multicultural past lingers in its architecture.

Toledo rewards those who linger. Whether you visit for a few hours or a few days, standing inside the Christ of the Light Mosque, where centuries of faith, art, and history converge, will be an experience that stays with you long after you leave.

Final Thoughts – Why the Christ of the Light Mosque Still Matters Today

In a city where history was often written through conquest, the Christ of the Light Mosque tells a quieter story—one of endurance. For over a thousand years, its walls have absorbed the presence of two faiths, standing as proof that architecture can outlast the divisions of its time. While many buildings were reshaped beyond recognition, this one remains a rare relic of coexistence, where Islamic and Christian elements intertwine rather than replace one another.

Walking through its arches, past Kufic inscriptions and beneath ribbed vaults, visitors experience more than medieval craftsmanship. They step into a dialogue between civilizations. From an Islamic oratory to a Christian chapel, the mosque’s transformation reflects Toledo’s layered past, a city once defined by cultural exchange. Preserved as a UNESCO World Heritage site, it continues to offer a glimpse into an era where artistic traditions were shared rather than erased.

Therefore, the Christ of the Light Mosque is more than a relic. It is proof that history is not a single narrative, but a series of overlapping stories. It reminds us that civilizations do not simply rise and fall: they build upon one another, leaving behind traces of belief, adaptation, and survival. And that in those layers, we can find not just glimpses of the past, but a lesson for the present.