Where Columbus Met the Crown: What Makes the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba a Must-See for History Lovers

The door swings open, and for a moment, you’re unsure what century you’ve entered. Cool stone meets your palms as you steady yourself. Above you, swallows thread the sky between watchful towers. Morning light glints off the water channels that snake through the garden, old and silent. You pause, perhaps unknowingly, in the very spot where Christopher Columbus once stood—hopeful, unproven, and on the edge of a world yet imagined. Before him sat Ferdinand and Isabella, cloaked in the weight of crowns and centuries, here in the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba.

![Gardens of the Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Ввласенко (Volodymyr Vlasenko). Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/4.-Gardens-of-the-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Ввласенко-Volodymyr-Vlasenko.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-SA-3.0.jpg)

It was in a small hall behind thick walls that the Genovese sailor unrolled his map and made a promise. A new route could be found, he claimed—if only granted ships. His audience: two monarchs who had just stitched together the last pieces of a long-fractured kingdom. History would call them Catholic, but here, they were simply rulers facing a decision.

The castle doesn’t impress with scale. Its beauty hides in corners—shadowed archways, coiled staircases, the echo of boots on stone. It’s a place built less for show than for strategy, and yet, somewhere between its towers and tiles, something lingers. Power. Faith. Risk. Not all turning points announce themselves loudly. Some revolutions start quietly, in places like these — cool, guarded, and lit by Andalusian sun.

Post last updated on April 9, 2025 (originally published on February 24, 2024) by Roberta Darie.

- Where is the Alcázar Castle in Córdoba and Is It Worth Visiting?

- A Palace of Many Faces: Layers of Time Within the Alcázar’s Walls

- Things to See Inside the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba

- Where History Meets Legend: Columbus and the Catholic Monarchs

- When to Visit the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba

- How to Make the Most of Your Time at the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs

- Why the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs is More Than a Historic Site

“You can never cross the ocean unless you have the courage to lose sight of the shore.”

— Christopher Columbus

![Gardens of the Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Eric Titcombe. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/10.-Gardens-of-the-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Eric-Titcombe.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-2.0.jpg)

Where is the Alcázar Castle in Córdoba and Is It Worth Visiting?

Tucked into the southwestern edge of Córdoba’s historic center, the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba sits quietly just steps from the Guadalquivir River. From the outside, it appears more fortress than fairy tale—its squat towers and thick limestone walls a reminder that beauty wasn’t always meant to charm. Sometimes, it was meant to defend.

History lovers don’t just come here for dates and dynasties—they come for textures, traces, atmospheres. They come for the worn grooves in staircases, for chambers that still hold the hush of decisions made long ago. The Alcázar offers this in abundance, quietly embedded within Córdoba’s UNESCO-listed historic center. It’s not theatrical. It doesn’t compete with grander palaces. Instead, it invites reflection. Every stone here seems to remember something.

What makes it special isn’t only who walked these halls, but how much remains. Roman mosaics still glint underfoot. A spiral staircase winds tightly into a tower once reserved for kings. In the gardens, irrigation channels from Al-Andalus still guide water between hedges and pools. And above all, there’s a stillness—an uncurated kind of truth. One that lets the past speak for itself.

A Palace of Many Faces: Layers of Time Within the Alcázar’s Walls

The Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba does not follow a single thread of history—it’s a tapestry, woven from ruins and reconstructions, politics and belief. Its walls don’t present a unified style because they were never meant to. They carry the memory of a city that changed hands, languages, and gods more than once.

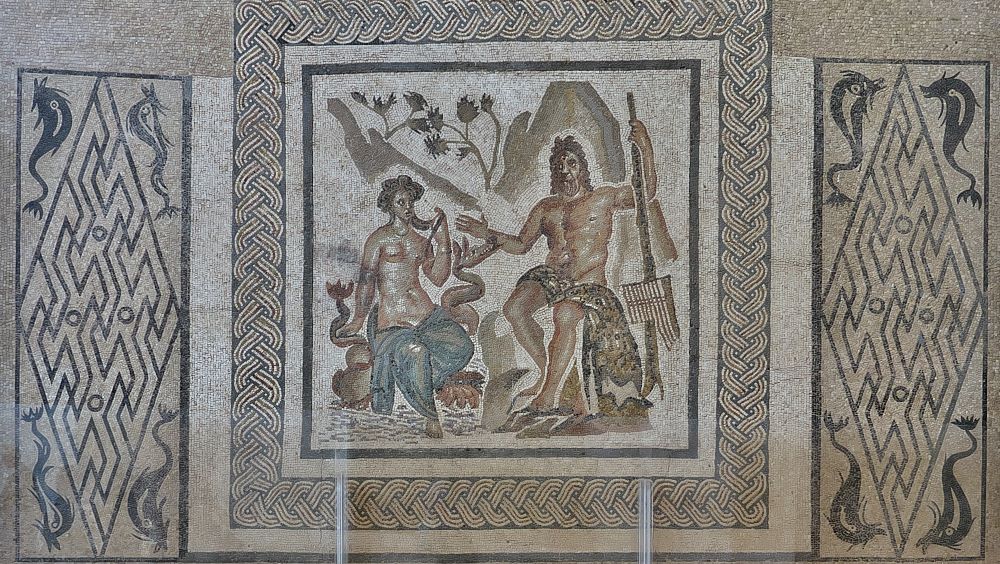

The land it occupies was once part of Corduba, the capital of Roman Baetica, and the remains beneath the castle—cisterns, paving stones, and a collection of finely crafted mosaics—are the clearest trace of that classical past. These mosaics, discovered in the early 20th century and now housed in the castle’s vaulted halls, were originally floor decorations in Roman aristocratic villas. Some depict scenes from mythology, others geometric patterns designed to impress guests while keeping cool underfoot.

By the 8th century, Córdoba had become the glittering capital of Al-Andalus. Though little remains of the original Islamic palace that stood here, the garden’s structure—its water channels, pools, and axial layout—recalls the engineering of the Umayyads, for whom paradise was both theological and architectural.

![Northwestern Wall of the Morisco Courtyard, Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Ymblanter. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/9.-Northwestern-Wall-of-the-Morisco-Courtyard-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Ymblanter.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-SA-4.0.jpg)

From Fortress to Memory: The Making of the Christian Monarchs’ Alcázar

The present form emerged in the mid-14th century. Alfonso XI, wary of noble revolts and seeking a southern power base, commissioned a new Alcázar that combined defensive solidity with royal function. The result is an austere complex of stone towers, vaulted chambers, and silent courtyards.

The name “of the Christian Monarchs” comes from the days when Ferdinand and Isabella used the Alcázar as a royal base—planning military campaigns, receiving envoys, and listening to a certain sailor’s pitch about unknown seas. But the story didn’t end there. Over time, the castle became many things: a tribunal during the Inquisition, later a prison, and now, a place of memory.

![Fountain in the Patio Morisco, Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: José Luis Filpo Cabana. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and GFDL.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/14.Fountain-in-the-Patio-Morisco-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Jose-Luis-Filpo-Cabana.-Licensed-under-CC.jpg)

Things to See Inside the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba

Stepping into the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba is less like entering a museum and more like crossing into a narrative. One told not in words, but in space, light, and texture. There’s no single path through it. The building unfolds in fragments: a vaulted chamber here, a watchtower there, sunlight slipping through a lattice window, a mosaic shimmering underfoot.

Each room holds a different chapter. Some speak of empire, others of exile. There are places where monarchs once conspired, and others where prisoners paced. You don’t need signs to feel the weight of what happened here—though they help. Much of the story is written in the stone itself: in the wear of the stairs, in the height of the doorways, in the stillness of the inner gardens. What follows is not a checklist, but an invitation: to look, to pause, and to let the building reveal itself on its own terms.

![Gardens and Palace of the Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: La Rossa. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/3.-Gardens-and-Palace-of-the-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-La-Rossa.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-SA-3.0.jpg)

1. Torre del Homenaje: Climbing the Watchtower of Kings

Within the walls of the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba, the Torre del Homenaje rises with quiet confidence. It’s not the tallest tower in Spain, nor the most ornate. But it holds something more enduring than grandeur: perspective.

The name — “Tower of Homage” — recalls its function. Here, fealty was pledged, strategy debated, oaths sealed. Built in the 14th century, its square shape and sturdy masonry reflect a time of uncertainty, when fortresses had to defend as well as impress. Today, the climb up its narrow staircase offers a different kind of reward.

At the top, Córdoba opens up like a map left in sunlight. The rooftops of the Judería stretch to the north; the curve of the Guadalquivir glimmers to the south. The Mosque-Cathedral looms nearby, its bell tower rising like a second sentinel. It’s one of the few spots in the city where Roman, Islamic, and Christian legacies can be seen in a single gaze.

The tower stands roughly 20 meters high (about 66 feet), and the steps—steep, worn, uneven—require a bit of care. But at the summit, history isn’t abstract. It’s panoramic. You don’t just learn about Córdoba here. You see it, framed by the same walls that once protected a kingdom.

2. Hall of Mosaics: Where Roman Gods Still Hold Court Beneath Your Feet

Tucked within the walls of the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba lies a chamber unlike any other in the fortress—a vaulted room where myth and empire meet underfoot. This space, now called the Salón de los Mosaicos, houses a collection of 2nd- and 3rd-century CE Roman mosaics, discovered in the 1950s during excavations beneath Plaza de la Corredera. Originally floor decorations from private domus—elite Roman homes—they were painstakingly lifted, preserved, and relocated here in the 1960s. Though detached from their original settings, they haven’t lost their voice.

Figures from classical mythology—Medusa, Neptune, Polyphemus—peer up from tesserae no bigger than a fingernail. One panel still shows Galatea riding a dolphin, her gaze unbothered by time. The craftsmanship is intricate: over 50,000 tiny stones arranged with enough detail to suggest movement, drapery, expression. It’s easy to forget you’re in a medieval castle.

Yet, their presence here makes quiet sense. The Alcázar, layered as it is, doesn’t reject the past—it absorbs it. These mosaics aren’t trophies; they’re continuities. Of a Roman Córdoba that still murmurs beneath the Christian stone.

3. Royal Baths: Echoes of Water, Whispers of Power

Beneath the fortified heart of the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba, there is a space where silence and stone conspire to preserve something older than conquest: the ritual of bathing.

The Baños Reales, or Royal Baths, were built in the 14th century during the reign of King Alfonso XI—designed not as decoration but as a necessity. Inspired by the hammams of al-Andalus, the complex follows a familiar (Roman) sequence: cold room (frigidarium), warm room (tepidarium), and hot room (caldarium), all arranged with precision to create a gradual immersion into warmth and stillness. Narrow skylights, star-shaped and unevenly scattered, pierce the vaults above, casting patterns that shift with the sun. Though adapted to Christian use, the baths retain their Islamic spatial logic. The flow of water, the balance of heat and coolness, the architecture that both reveals and conceals—these design elements survive as echoes of a Córdoba that once rivalled Damascus.

There are no statues here, no marble grandeur. What you find instead is intimacy: a space carved for reflection, diplomacy, or perhaps indulgence. In these low, vaulted rooms, decisions were made, alliances forged, and bodies—wearied by rule—rested. To visit the baths is to descend, both literally and historically, into the private lives of rulers. And in that quiet descent, the Alcázar speaks not of crowns, but of custom.

![Royal Baths at the Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Turol Jones, un artista de cojones. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1.-Royal-Baths-at-the-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Turol-Jones-un-artista-de-cojones.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-2.0-844x1024.jpg)

4. Gardens: Geometry, Memory, and the Murmur of Water

Step outside the stone chambers of the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba, and the air changes. It softens. Fragrance replaces echo. Light pools across still water. And suddenly, history begins to bloom.

The gardens stretch southward in measured symmetry: hedges trimmed with precision, walkways lined with cypress and palm, pools reflecting towers above. Their layout, while expanded over centuries, remains rooted in Islamic Garden design, where paradise was imagined as a walled enclosure—cool, ordered, and shaped by flowing water.

Three terraces descend gently toward the river, each framed by rectangular ponds fed by narrow irrigation channels. These acequias, inherited from Al-Andalus, don’t just serve form—they serve function. Even in the heat of Córdoba’s summers, the gardens hum with life. Orange blossoms perfume the breeze. Fountains chatter. Swallows dart low over the water. There is movement, but no hurry.

The Catholic Monarchs chose this garden not only for its beauty, but for its balance. Here, within rows of citrus and still pools, they received envoys, weighed military campaigns, and in 1486, listened—perhaps skeptically—as a Genoese sailor spoke of distant shores. The setting made sense. Order calms the mind, and water, always moving, invites vision.

Today, the gardens unfold across 55,000 square meters (about 13.5 acres) of terraces and green geometry. You could walk them quickly, tracing straight lines from one fountain to the next. But if you pause—beneath the shade of an orange tree or beside a murmuring pool—you may glimpse what others once came here seeking: not just a moment of rest, but a clearer view of the world.

Where History Meets Legend: Columbus and the Catholic Monarchs

It was a spring day in 1486 when a little-known navigator from Genova entered the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba with a proposal as audacious as it was uncertain. Christopher Columbus—Cristóbal Colón in the Castilian of the court—had no map to prove his claim. Only calculations, conviction, and a plan to reach the Indies by sailing west across an uncharted ocean.

Europe was shifting. The medieval world, shaped by feudal bonds and crusades, was giving way to the early stirrings of the Renaissance. Books spread ideas. Cities grew. And kingdoms—especially those newly unified, like that of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile—looked beyond their borders for power and trade. The conquest of Granada was still underway, but their gaze was already turning beyond the Strait of Gibraltar.

![Statues of the Catholic Monarchs and Columbus, Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Pablo Rodríguez Madroño. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/13.-Statues-of-the-Catholic-Monarchs-and-Columbus-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Pablo-Rodriguez-Madrono.-.jpg)

Vaulted Ceilings, Uncharted Waters

Columbus came to Córdoba because the court was here, using the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs as its base during the final stretch of the Reconquista. He likely made his case beneath vaulted ceilings still heavy with strategy and prayer. He did not receive approval that day. But this meeting—this very place—is bound to the moment a New World was quietly set in motion.

Seven years later, with Granada conquered and the monarchs firmly in command, that long-delayed journey finally began. On August 3, 1492, Cristóbal Colón set sail from the port of Palos de la Frontera, in southern Spain, aboard three small ships: the Santa María, the Pinta, and the Niña. After nearly two months at sea, on October 12, land appeared on the horizon—an island in the Bahamas, though he believed he had reached the Indies.

It started far from any coast, in a quiet Andalusian Hall where ambition met hesitation. Today, the weight of that first encounter still lingers in the air. And in the architecture of the Alcázar, we glimpse more than stone and symmetry. We see the hinge of two eras: the fading medieval world, and the modern age it would unknowingly give birth to.

![Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/11.-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Jose-Luiz-Bernardes-Ribeiro.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-SA-3.0.jpg)

When to Visit the Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba

Timing matters, especially in a place as sun-soaked and storied as Córdoba. The Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba can be visited year-round, but to experience it at its most generous, come in spring or autumn. From March to May, the city blossoms. Temperatures hover around 22–28°C (72–82°F), the air is scented with jasmine and orange blossom, and the light softens the fortress’s limestone into gold.

If your travels align with May, don’t miss the Festival de los Patios. It’s one of Córdoba’s most beloved traditions. Local homes open their private courtyards, filled with geraniums, fountains, and color. The Alcázar’s own gardens feel even more harmonious in this context—part of a wider story told in petals and stone.

![Partial View of the Gardens, Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Jebulon. Released into the public domain.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/5.-Partial-View-of-the-Gardens-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Jebulon.-Released-into-the-public-domain.jpg)

How to Make the Most of Your Time at the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs

Plan to spend at least two to three hours exploring the Alcázar itself. You can pair it with the Mosque-Cathedral, located just five minutes away on foot, for a full half-day devoted to Córdoba’s layered past. Consider starting early to beat the crowds—or staying late, when the stone cools and the light slips low.

For a more immersive experience, guided tours offer insight into what the walls can’t say aloud. Night visits, occasionally offered in warmer months, reveal another dimension: shadows, silence, and stories retold by moonlight. This isn’t a place to rush. The Alcázar rewards those who slow down, look twice, and listen.

![Panoramic View of the Alcázar of the Christian Monarchs, Córdoba, Spain [Edited Photograph]. Credit: Berthold Werner. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.](https://itinerartis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/6.-Panoramic-View-of-the-Alcazar-of-the-Christian-Monarchs-Cordoba-Spain-Edited-Photograph.-Credit-Berthold-Werner.-Licensed-under-CC-BY-SA-3.0.jpg)

Why the Alcázar (Castle) of the Christian Monarchs is More Than a Historic Site

History is often taught through dates and declarations. Yet, sometimes it begins in the lingering pause before a question is answered. The Alcázar (castle) of the Christian Monarchs in Córdoba doesn’t proclaim its importance— it waits for you to discover it, in the folds connecting shadows, hopes, and silences.

To walk here is to trace the contours of power at its most fragile—negotiated in whispers, recorded on parchment, tested by time. The garden paths and vaulted chambers aren’t just remnants. They’re thresholds. Between ancient empires and new worlds. Between the certainty of stone and the mystery of vision.

What lingers isn’t conquest, but complexity. Layers. Roman beneath your feet, Islamic in rhythm, Christian in reach. Each culture left its note, but none stood alone. That, perhaps, is the quiet truth the Alcázar offers: the future is rarely forged out of nothing. It is built—unevenly, inevitably—upon the dreams of the ones that came before.